Synopsis

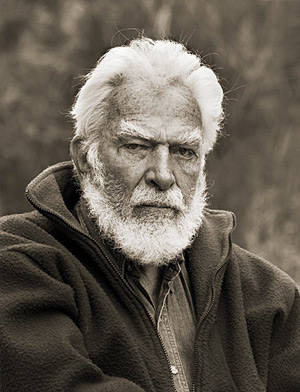

Preeminent conservationist David Brower called him his conscience: in the 1950’s when the Bureau of Reclamation proposed two dams in the Grand Canyon—one at Marble Canyon and the other at Bridge Canyon—the late Martin Litton made sure the Sierra Club didn't acquiesce. Martin believed the best way for people to understand how important it was to preserve the Grand Canyon was to have them experience this secret world from the river, but not in just any boat. Martin pioneered whitewater dories on the Colorado River in the 1960’s and started a proud tradition of naming the boats after wild places that had been lost or compromised by the hand of man. Now, some 50 years later, America’s open-air cathedral faces continued threats from development and mining and it’s up to all of us to ensure the crown jewel of our National Park system is protected now and for future generations. Martin’s Boat is a film that honors the legacy of Martin Litton and follows the newest boat in the Grand Canyon Dories fleet, the Marble Canyon, on its maiden voyage down the legendary Colorado River through the grandest canyon on Earth.

Support the Greater Grand Canyon Heritage National Monument

“Every 15 or 20 years, it seems, the canyon forces us to undergo a kind of national character exam. If we cannot muster the resources and the resolve to preserve this, perhaps our greatest natural treasure, what, if anything, are we willing to protect?”

— Kevin Fedarko

Urge President Obama to put a permanent stop to uranium mine pollution in Grand Canyon National Park and protect the Canyon’s sacred waters by proclaiming the Greater Grand Canyon Heritage National Monument.

Martin's Boat

by Pete McBride

It is just past six a.m. and the dawn rays are kissing a frothy spray dancing above the rapid ahead. The wind and hundred-plus desert temperatures are still sleeping. That reprieve of gusty, furnacelike heat tempers my nerves little. My mouth is desert dry thanks to adrenaline coursing through my body. I try to focus on the sage advice the silverback boatman shared minutes earlier.

On shore, it all made sense, but as we slide over the lip of Lava Falls, mile 178 on the Colorado River inside the Grand Canyon, everything is more chaotic. It is my first time rowing a raft down this storied section of river. That alone is enough to send my heart into a fear-filled dance, but what complicates things is that rowing is secondary to making a short film about a river legend I’ve never met.

I’m running last in a flotilla shadowing the maiden voyage of a fiberglass dory—built amidst sweat and love over the last year—down this undammed 277-mile stretch of the “American Nile.” The goal is that this boat and the footage will remind many of the spirit of a guy who enabled river trips like this to exist today—Martin Litton.

We slip over the first cresting wave of Lava and see the river angrily detonating before us. On river left is “death and destruction,” as Martin once described the left line, and on the right, “eternal darkness.” Somewhere in the middle is a “silvery path,” but somehow, amidst the predawn scout, the filming and my nervous over-thinking, something has gone wrong.

When describing Martin Litton, many boatmen say, “he carried an angel on his shoulder,” which often rescued him from rapid ruin, even when he flirted with it.

I could use that angelic friend of Martin’s now. A less than silvery path lay ahead. I’m way off course.

I could use that angelic friend of Martin’s now. A less than silvery path lay ahead. I’m way off course.

In 1939, Martin Litton first peered over the edge of the Grand Canyon. “It never occurred to me,” he said in a TV interview years later, “that I’d go on the river…you might as well go to the North Pole.” But a mere decade later, while working as a writer for the Los Angeles Times, he documented an expedition negotiating Lava Falls. By 1955 he was back, rowing a fiberglass cataract boat and by 1962, he’d imported Oregon drift boats, the original dories, to the canyon.

Despite the logistical advantages of inflatable boats (Martin preferred the aesthetic of dories) in 1971 an accidental river company blossomed—Grand Canyon Dories. With it came a deep voiced, wild boatman named Martin with an angel on his shoulder.

While many in the Grand Canyon know of Martin for his dories and legendary river tales, I grew up knowing him for something else. In the late 60s, Martin played a role in keeping the Grand Canyon free from two colossal dams—Marble Canyon and Bridge Canyon. His impassioned speech to the Sierra Club board triggered David Brower to fight the Bureau of Reclamation.

Having grown up on the Colorado River and following its water challenges from the headwaters in Colorado to its dry delta in Mexico, the story of the Marble Canyon Dam defeat—was the quintessential David and Goliath. And as Brower put it, “Martin was my conscience” that steadfast fighter who refused to compromise.

I always wanted to meet Martin. I knew he was aging but when someone rows a dory through Lava Falls at the age of 87, you expect them to stick around for a while, possibly forever.

But sure enough, right when I was thinking it was time to meet this river-running legend and appear at his doorstep, Martin was gone. The hero of the Grand Canyon had rowed onward.

But last spring, I was invited to meet the spirit of Martin via some of the people who knew him best—his friends and river family—the boatmen and women who worked with him, grew up in his boathouse and carry his passion for the Grand Canyon forward.

For two weeks, I follow the newest dory in Martin’s fleet—a sculpted piece of artwork dubbed The Marble Canyon built in honor of that place Martin helped save. In Litton fashion, the boat carries a name of a special place, either gone or protected. Duffy Dale, the boat builder and second generation dory guide himself spent five months crafting the dory to perfection. To remind passengers and boatmen to come, a wild-eyed photo of Martin resides inside the hatch.

We glide and splash downstream, past the dam-free Marble Canyon dam site, the roaring twenties, and row the shadows of the inner gorge. Around each ancient oxbow, I see glimmers of Martin’s spirit joining us, in the eyes and smiles of those that loved him.

When we reach Lava, I watch Martin’s early boatman—Andre Potochnik, Mark ‘Moqui’ Johnson, make the line easily. The next dories do the same. Duffy plunges the Marble Canyon right down the seam, perfectly.

With my less experienced rowing skills at the helm, we slip over the lip last and it is clear Martin’s ‘silvery path’ is too far right. I’ve cheated the left line too far left. ‘Death and destruction’ lies ahead. Our raft slams into the entrance wave and immediately stops, reverses, and turns sideways nearly throwing me and my two film crew from the raft. My right oar shoots skyward and I vanish into an angry churn of whitewater foam. Flipping is imminent.

But perhaps the grandfather of dories, that white-bearded river giant, decided to watch that morning. Or maybe it was his angel. But something, somehow, stalls the flip, spins us back left, and carries us toward that silvery line…backwards with one oar. The “eternal darkness” of the ledge hole passes and we crest the shoulder of the Chub and Big Kahuna waves and come out soaking, stifled and screaming with joy.

But perhaps the grandfather of dories, that white-bearded river giant, decided to watch that morning. Or maybe it was his angel. But something, somehow, stalls the flip, spins us back left, and carries us toward that silvery line…backwards with one oar. The “eternal darkness” of the ledge hole passes and we crest the shoulder of the Chub and Big Kahuna waves and come out soaking, stifled and screaming with joy.

Downstream, boatmen and passengers readily celebrate the man who started it all—and fought to keep the river flowing so our little boats could crest its waves. And with each mile, I think more how I wish I’d met Martin, but feel lucky to know and see his spirit alive and well on the river with the dories of the Grand Canyon.

Read more about the legacy of Martin Litton.

About the Filmmaker

Native Coloradan Pete McBride has spent almost two decades studying the world with a camera. A self-taught, award-winning photographer, writer and filmmaker, he has traveled on assignment to over 70 countries for the publications of the National Geographic Society, Smithsonian, Outside, Esquire, Stern and companies like Patagonia, Microsoft, The Nature Conservancy and more.

After a decade working abroad and completing a journalism fellowship at Stanford, Pete decided to focus his cameras closer to home on a subject closer to his heart. Combining his passion for aviation and his belief in conservation, he spent over four years documenting his local river — the Colorado. This journey culminated in a coffee table book: “The Colorado River: Flowing Through Conflict”, and a series of short films “Chasing Water” “I AM RED”. He now focuses his lenses and energies on watershed issues and related stories around the world to raise awareness about water challenges.

His work as a photographer and filmmaker have garnered awards from Pictures of the Year International to the Banff Mountain Festival and many more. American Photo Magazine named Pete as one of the top five water photographers in the nation and In 2014 after completing a story following the length of India’s Ganges River, The National Geographic Society named McBride a “freshwater hero”.

When not lost on assignment or doing public speaking, you can find McBride exploring the creeks and mountains around Colorado, or practicing mandolin on his back porch in Basalt, Colorado.

You can see more of Pete’s work at: www.petemcbride.com.

Guiding Life's Greatest Adventures since 1969

At OARS we strive to enrich people ’s lives by providing outstanding outdoor adventure experiences. We personally encourage and actively support awareness, deeper appreciation, and preservation of our rivers and natural ecosystems. Our trips are great adventures that emphasize heightened attentiveness to human impact on the environment.

In partnership with our guests, OARS has contributed more than $3.5 million in donations and fees toward the preservation of the environment and to various conservation initiatives since the company was founded in 1969.

For more information on our commitment to responsible travel and to view our collection of award-winning nature-based adventures, visit the OARS website: www.oars.com.